Very Fine Day #24: Mary Robertson

"There’s no shortage of television that's been made about Britney Spears."

Very Fine Day features weekly interviews with writers, creators, reporters, and internet explorers. Learn more about the people who keep the internet humming – and check out previous editions here. Subscribe now and never miss an edition.

“Her ascent to superstardom was not so much preordained but perhaps almost inevitable. And that the culture that was receiving her in ways that weren't generous – that too was almost inevitable.”

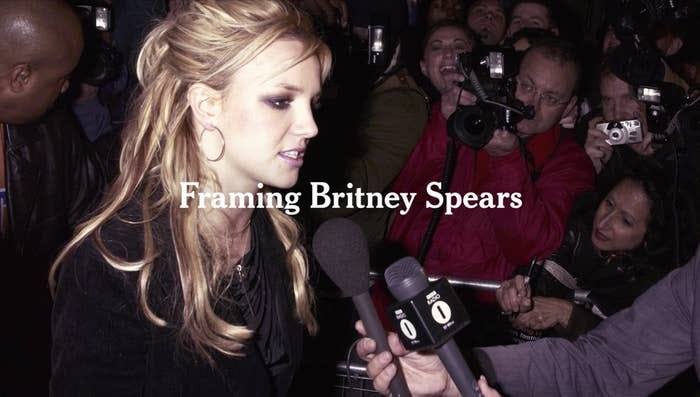

Mary Robertson is an Emmy Award-winning showrunner and director. Presently she works as the showrunner of The New York Times Presents, the anthology documentary series from the New York Times, Left/Right, FX and Hulu. Her most recent effort for the series is “Framing Britney Spears”, a critically-lauded documentary that has broken ratings records around the world and touched-off a reckoning on Spears' treatment, misogyny and tabloid culture.

Mary helped create and executive produce “The Weekly”, whose first season garnered nine Emmy nominations and four wins, and also helped executive produce Showtime’s documentary series “The Circus,” focusing on the 2016 Trump / Clinton US presidential election.

We spoke for about 45 minutes, mulling over what it takes to craft a great non-fiction narrative, the collaborative process of documentary, and, of course, the many decisions made in the creation of “Framing Britney Spears.”

If you enjoy this interview and want to read more just like it, subscribe for free today.

Also, check out the Very Fine Day Instagram!

VFD: Where are you? Are you in New York?

Mary Robertson: I am in upstate New York.

VFD: What's that like? Where from New York City are you?

Mary Robertson: I'm about two hours north of New York City and we relocated up here at the beginning of the pandemic, for what we thought would be a temporary spell. It's a similar story, but we've been here since March of 2019. And my husband's father lives up here as well, which was part of the reason why we chose to be up here. He was quite sick. So, one of the few silver linings of the pandemic was that we were able to be close to him during this period of his infirmity.

VFD: Right, of course. Where did you move from?

Mary Robertson: I live in Brooklyn most of the time, and we'll be back there in September.

VFD: Sounds like you’re looking forward to it.

Mary Robertson: I am, I definitely am. I miss the people of my city, and I'm a native New Yorker. And there's something about the environment that certainly stimulates me automatically. When I walk back into New York City, I feel just a little bit more alive.

VFD: Oh so you’re a native to New York City?

Mary Robertson: Yeah, in Brooklyn.

VFD: So you've watched it fully become “hip Brooklyn” I'm guessing? How do you feel about that?

Mary Robertson: I mean, listen, I think it's less hospitable. The city, generally, is a less hospitable environment for aspiring artists or aspiring anything. I think it's harder to carve out space to live and work when you're not a mid career professional, or when you're not coming from a privileged background.

But the city still has – and being in upstate New York has reminded me of this –so much more diversity and it forces you to exist in proximity with people who are unlike yourself. You cannot ride the subway without, quite literally, your nose in the armpit of someone who probably doesn't lead an identical life. And I think that's so healthy for humans.

VFD: It's pretty wild. One thing I always think of, when I think of New York, is when I was last there. I used to sit out on the apartment balcony at night time and just listen to all of the air conditioners. The hum. It wasn’t a bad thing, it was just an unreal sound that I don't think you could replicate in any other way. But it's a great place.

So then how would you classify what you do? Are you a producer, a director, a showrunner?

Mary Robertson: Yeah, sure.

Right now I work as the showrunner of the anthology documentary series called “The New York Times Presents”. Our most recent, or our sort of “greatest success” to date, has been the film that we made about Britney Spears, the documentary “Framing Britney Spears.”

Mary Robertson: I think we also achieved a degree of impact with our film “The Killing of Breonna Taylor”, which came out recently as well.

So, prior to my work as the showrunner of “The New York Times Presents” I've worked as a showrunner and executive producer, as a director, as a producer, but always in nonfiction film and television, which is one of my great loves.

And, y’know, regarding what a showrunner does: in nonfiction I think there's a lot of variants depending upon the size of the endeavour, right? It's different if you're overseeing 30 episodes of “The Real Housewives Of Whatever” versus what we're doing, which is a more boutique operation where we are working to hand-stitch five to ten feature length documentaries a year.

In that case, it's really working to support the team and to provide a degree of consistent editorial oversight. So to help our team move towards our goals as journalists and as storytellers, and I think really when we're doing our jobs well – for our series – we're bringing great journalism to the air. And we're also encasing it in great narrative.

VFD: Do you have a journalism background? Is it a fascination in journalism, or is it more the nonfiction storytelling that's kind of crossed over with The New York Times?

Mary Robertson: I came to documentary through an obsession and love with cinema, and through an obsession and love with reality, which of course now when you hear “reality” you think “reality television” – and that's not what I'm referring to.

VFD: No Kardashian stuff for you?

Mary Robertson: No, no… I always believe that truth is stranger than fiction.

I was so just endlessly fascinated and beguiled by nonfiction and the stories that exist around us. And, y’know, I've always wanted to mine and plumb those depths.

I've been really fortunate that my professional trajectory has sent me towards journalism and that I've been able to work alongside some of the best journalists in the business. And one of the great thrills of my job now is that I'm able to learn more about journalism and better my craft as a journalist a little bit every day.

But I do really try – to the extent that I'm bringing a little piece of myself to this endeavour – I do really try to encourage my team to encase their journalism in narrative. I really think it's with story that we engage an audience, and it's through engagement that we have impact.

I could go on and on…

VFD: Well, when was it that you realised that was something you could do?

You have this emotional connection, right, and you have this feeling of: I think the truth is better than fiction. I like telling these stories. But was there a particular project or moment where you're like: Oh, this is a job. Or: This is a thing that I could just continue doing for the rest of my life, in a bunch of different ways.

Mary Robertson: Yeah, yeah. I hope I can continue doing it for the rest of my life! I’m really fortunate right now.

Was there a particular project? Well, I think it's an evolving objective, and I've never felt in a better position to be able to realise it than I am, and we are, right now with “The New York Times Presents.”

It is really, I think, this idealised marriage between narrative and journalism.

I had a really positive experience working on a series called ‘The Circus”, which you may or may not have heard of. I was part of the executive team which created and developed this series and launched it in 2016. And the promise of that I thought was quite novel, in that we were really looking to immerse ourselves in the ecosystem that is created on the campaign trail.

And of course, this was the year in which Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump ultimately faced off.

VFD: Yeah, very relaxing then?

Mary Robertson: It was not relaxing, ha. Definitely not relaxing.

So the promise of the show was that we would immerse ourselves in this ecosystem and that we would bring viewers into this world, and there would be great proximity to this universe, and you would come to understand the people who populated it and the ways in which they interacted with each other and how all of this was influencing this enormously consequential contest – a contest that could not be of greater consequence, I think, inarguably.

And then the promise was also that we would do it in a way that was timely, and we worked to both film, and edit, and release these episodes the week that we were filming. So there was nothing out there that we had filmed three weeks ago. It was always the same week.

And then beyond that, we wanted the form to be cinematic. We wanted to move past some of the conventions of network television news – certainly move way past them. Anything that felt presentational, or that felt static, that wasn't what we wanted. We wanted to bring you into scenes with characters. And I think we achieved it.

I mean, you'll look at points where it's more successful than others, but moving towards that as a goal helped us align our work. So that gave me a taste of what one can achieve with this marriage between narrative and journalism. And that was a form of journalism, too. The practice was a bit different, but it was journalism.

VFD: So wait, sorry, was that the first time you did video stuff?

Mary Robertson: No, I'd been working only in television and film.

VFD: Oh, of course, of course.

How do you make those decisions: how you wanted it to be cinematic, and you wanted it to look a certain way, and feel a certain way? Is that based on inspiration you see from other documentaries? Or is that just from going: This doesn't exist. Why doesn't this exist?

Mary Robertson: Yeah, well, I don't think that I, or we, invented it. So it does exist. But in the case of “The Circus” it didn't exist on that timeline. No one was trying to do that every week. And on the campaign trail? That was ambitious and terrifying for those who were trying to do it.

And I think they're great examples. This year there's this film “Collective” out of Romania. And it follows some investigative journalists there as they were investigating the fallout from a fire in a nightclub. After this fire, a number of victims had been sent to a hospital and then died under confusing circumstances. And in this film, this documentary, these investigative journalists probe the conditions in the hospital. I don't want to spoil it, but their revelations are chilling. And you're there. It’s a truly incredible documentary.

But you're there, and the camera is there, as they connect the dots. And it's riveting. It's absolutely riveting. And I think that serves the public interest in manifold ways. And, y’know, I really enjoyed the film “Spotlight”. And I love “All the President's Men”, like so many people. But this was as cinematic, or as gripping, as either of those films. Maybe more gripping than “Spotlight”.

VFD: Do you think about unwrapping that narrative when you have to work with something like, say, the Britney Spears documentary? Which is obviously using a lot of past footage and past experiences. And it still being able to create a narrative that unwraps it in that way, so it feels like you're walking along with it?

Mary Robertson: Do want to ask the question in a slightly different way? I'm not sure I totally get the question.

VFD: Sorry, no, I just mean: how do you think about that? Do you want that continuously in the films that you make? Do you want the audience to be – not in the dark – but discovering things only when you're ready for them to discover them?

Mary Robertson: Totally. I think considering the way in which we structure the introduction, and the development of information, is of paramount importance when we're thinking about how we build documentaries. And I'll reference “The New York Times Presents” and we can talk about “Framing Britney Spears”, in particular.

I think with that film it was really important to me that we root the film in the present. So we begin the film with an understanding that there's controversy rolling around the conservatorship. But then we very quickly move back to the beginning of Britney's professional life, which was when she was a child.

VFD: Yeah,

Mary Robertson: So you see her performing on “Star Search,” and you see her manifesting with this, I think, really incredible voice and this incredible charisma. And you see her, also, being met – I would say – rather ungenerously by Ed McMahon, the host at the time. And y’know, she's a kid, and he asks her whether or not she has a boyfriend. And then puts himself into the question as well.

Mary Robertson: And I think by putting, for example, that clip towards the top of the show, what the audience can do and what I was hoping they would do is look at that clip and say: Here's a woman, who's a girl, who's presenting with extraordinary talent.

And by way of that you start to root for her and if nothing else understand that she was presenting with extraordinary gifts. And she was being met in this moment by a culture that maybe – and ungenerous is not perhaps the best way to put it – but she was being met at that moment by a culture that I think didn't know how to receive her. It didn't know how to receive her gifts. And certainly she was being sexualized to some extent.

VFD: Definitely

Mary Robertson: And you see in that clip that her ascent to superstardom was not so much preordained but perhaps almost inevitable. And that the culture that was receiving her in ways that weren't generous – that too was almost inevitable. That the seeds were planted early on and that conflicting and intersecting arcs would sort of launch around this moment.

VFD: Yeah,

Mary Robertson: I think it was really important to me as well, in the film, to make sure that we presented her story then in a linear manner and that we didn't quickly fly by the part of her life that precedes these really public and somewhat iconic incidents: The so-called “umbrella incident”, and when she shaved her head.

I wanted us to move through the time before those incidents. And I wanted to do it in a linear manner, but I also wanted to do it at a pace that allowed you to really feel what she may have been experiencing, to some extent, albeit from a distance.

To feel the way the culture was moving around her and as an audience member to really experience an accretion. To really experience some build and some rising understanding of what she was doing, what she was capable of professionally, but also how the culture was meeting her, and how the culture was treating her, so that by the time you're in these iconic moments you're bringing heightened understanding, and perhaps new sympathies and empathy to your understanding, of what might have influenced and impacted that moment – and her in that moment.

I should say, of course, that I've been using the first person a lot. But this film was absolutely a massive collaboration. And, y’know, there are 10 people who were absolutely essential to the film’s success, and everyone contributed in big ways.

VFD: How does that work? Like, did The New York Times come to you and say: Hey, the next story is Britney Spears, because we have a bunch of journalists and they've figured all this stuff out.

And then you go: OK, cool. And then you run away and try to figure out: OK, how do we tell the story the best way?

Or is it more of a, like: Excuse me, I have an idea…

Mary Robertson: In this case we have, as a documentary unit, frequent meetings in which we discuss new ideas. Pitch meetings, if you will. And in one of these meetings my colleague, Liz Day, or actually before the meeting, she sent an email saying: What if we did “OJ Made in America”, but for Britney Spears.

And that was the pitch in a nutshell. I thought it was a brilliant pitch.

I think it's a brilliant pitch in part because one of the many things that we loved about the “OJ Made in America” documentary series is that it began its storytelling decades before the trial. Many people had deep familiarity with the trial but not familiarity with the history of race relations in Los Angeles decades before the trial. So they begin their storytelling decades before. And by the time you were then revisiting the trial you were bringing a new understanding and new empathy to it – a new perspective to it.

Of course, the other thing that film did so brilliantly… well one of many things – that film did almost everything brilliantly. I'm one of many people that worships that film.

VFD: Yeah, you seem like a big fan.

Mary Robertson: But it just approached the subject matter with ambition and sweep, right? So there's a scale to it that was appropriate and inspiring. So when I heard this pitch, I thought: I love this idea of beginning the Britney Spears story decades before these infamous incidents.

And also, it used to be that many people when they thought of Britney Spears they first thought of her nadir. This public nadir, at least, in 2008. And I thought that that would be a great approach. And then also the idea of bringing real ambition and scaling up our exploration in the manner of “OJ Made in America.”

Of course, they were seven hours and we were 73 minutes, so there's some difference there. But that was very inspiring to me. And the idea of simply bringing journalistic rigour to a subject matter that many had trivialised. That was honestly appealing, too.

So I did my part – and I'm one voice in the room – but I did my part to express my support and enthusiasm for the idea. And then our next step is to assign a producer to dig in and do some more research. My colleague, Lora Moftah, she dug in. She learned more about the conservatorship – this was still very top level – she learned more about the passionate fans who are advocating on behalf of Britney, she learned more about some of the paparazzi who have been expressing remorse, perhaps, around their role in Britney's trajectory or the way in which they may have influenced her. And we put together a treatment, based upon Laura's research, and we shared it with our network partners at FX and Hulu. They quickly caught onto the idea, saw its promise, and gave us the green light, which was terrific. And then we handed it off to Samantha Stark, who of course is the director and producer of the film. And Samantha brought her singular, brilliant, perspective to bear upon it.

Samantha, I think, became very quickly interested in chronicling the fan movement and then truly doing what we could to investigate the conservatorship – even though we were cautioned early on: You'll never really get very far in this endeavour. All the doors are closed. People don't talk. The court records are sealed.

But we resolved to try.

And Samantha also had the really smart idea to very deliberately approach some of the women executives who had surrounded Britney, in her early professional life, in part because she felt that she hadn't often heard from them. And she watched a number of other documentaries – there’s no shortage of television that's been made about Britney Spears – but Samantha felt that the female point of view was missing from these other films and she wanted to simply see what these women would say if she approached them. And I think that was ultimately really productive and bettered our journalism. She built great relationships. Eventually, she made her way to interviewing Felicia Culotta, which I think was really integral to the film's presentation.

VFD: And Felicia, that’s Britney’s assistant?

Mary Robertson: Yeah, yeah.

VFD: OK, right. So I've watched this documentary twice. I watched it when it came out and I watched it again this week. And what I wrote down while watching it for the second time was – and there were a few things, but one of them – was just “horror movie”.

Like, if a documentary is made to bring emotion up in people then definitely, amazing, it's done a great job there. But what I was thinking about, when I was thinking about the way it made me feel, is what it must be like to put stuff like that together.

It’s very heavy stuff, right? And that's not just the Britney thing. We could also talk about the Breonna Taylor film as well. Even the Trump vs. Hillary election, you're dealing with very intense emotional stuff, and you're having to go through so much footage. If I watched 70 minutes, what have you looked at, 7000? So it's like: how do you approach that? What is the secret to being OK with just seeing so much of someone's life fall apart, or someone's life not going the way they planned? And if you're responsible for crafting it, you have to digest it all. What comes from that?

Mary Robertson: I mean, it's a good question. I don't think I'm a master of managing my emotional response to the material necessarily. I don't know that there's a secret, necessarily. Some material simply devastates.

I think it is true, though, that the more one watches something the more inured one becomes to its impact. And I think one of the things that I and my colleagues can do - and owe our audience - is to remember the way we felt when we watched something intense for the first time.

I really do try to take really careful note of what I'm feeling when I'm watching. This is when I'm watching a single clip for the first time, but certainly also when I'm watching what we would call a rough cut: everything assembled for the first time.

I want to take really careful note of what I'm feeling. Even if it's just a little hint of an emotion or a hint of confusion. Because I think that if I'm feeling it, I'm not the only one who's going to feel it. But my response to the material will change through time.

And we had an absolutely brilliant editorial team, including Geoff O’Brien and Pierre Takal, who worked on editing the film and were really responsible for a lot of what you might consider to be the writing, or the arrangement of words, in the film.

And I think that, yes, we all watched the film probably 100 times at least. I mean, it changes. The final film in its final form – we didn't watch that 100 times – but we've watched various cuts of it 100 times and you really, I think, have to work hard to bring the original perspective to it.

I had a teacher in film school who said: editing is losing perspective through time. And I know other editors – and in print journalism this means something a little bit different – but I know editors in film who, if they're about to screen a cut, will stand up, leave the room, walk around the block, walk around the home, and then come back and sit in a new chair, just so they can stimulate fresh orientation towards the material.

I don't know if that directly answers your question, though, about how we are to ethically respond to traumatic material and how to do it in a way that's emotionally intelligent, too.

I think each case is a little bit different. We just have to remind ourselves that we're dealing with real people's lives and sometimes you work on film in a dark room with four other people and it's easy to lose track of understanding that tens of thousands – or millions of people – might see this one day and that will impact the people in the film.

We need to think carefully about that, which is not to say that as journalists we “pull our punches”, necessarily. Like, accuracy is our objective. But we need to proceed with sensitivity.

VFD: Yeah, I think another thing I noticed on the second watch was, well, hmm…

So the apparent exploitation of Britney Spears is obviously distressing. And it is particularly now in the 2020s. And I think one very nice touch was the decision to open the documentary with the TikTok videos. Being like: Look at these kids who were not even born when Britney Spears was a thing, or at her peak, just talking about Britney Spears.

But if the documentary is about exploitation, we’re also seeing this whole generation of kids beginning to – I don't want to say use – but they are exploring Britney Spears and her story publicly. And they are getting rewarded in the same way: with likes, with views, and with followers.

And the documentary is showing off the timeline of someone's life so that you can tell a story, right? And I guess, did you ever consider the potential for it to be exploitative? Not exploitative, but to see that was a possibility, right? This person was exploited, ravaged by media, and now we’re making media about the exploitation. It just kind of seems to eat itself again, and again, and again.

Mary Robertson: Yeah, I think we have to be mindful that we are working to serve the public interest. And if there's a truth – and we can talk about some of the particulars of Britney’s situation – but if there's a truth in Britney’s case that's been shrouded or covered then it is ethical, responsible, and righteous to some extent to work to unearth that which has been covered.

And I think we've learned since the film came out, through my colleagues Liz Day, Samantha Stark, and Joe Coscarelli, who have published a number of fantastically illuminating print pieces on Britney Spears. And of course Ronan Farrow and Jia Tolentino had a piece out as well that advanced our understanding. And of course now Britney herself testified and her testimony was heard, and so we now clearly understand that she does not want to be in the conservatorship, right?

VFD: Yeah, I think we can say that.

Mary Robertson: Like, she does not want to be in this. And that was not the dominant narrative or understanding before we started the film. Which is not to say that we're solely responsible at all for changing the understanding of that, but when we started our reporting we often heard: We don't know for certain but there's reason to believe that she's basically satisfied with the arrangement. It works for her. She has been productive. She has managed to achieve a fair amount professionally and earn a fair amount professionally under this construct. She probably has needs that make it somewhat essential support to her.

That was the narrative that we heard. That was certainly not the narrative that the Free Britney army was espousing. But it was a narrative that was out there. So I think we understand better.

So I guess that's a long way of answering the question about: do we consider whether or not it would be exploitative? And I think there was concern, and Samantha was really great at being very sensitive to this, and bringing up this conversation consistently.

There was concern about how we could approach this given that Britney herself wasn't participating. And one thing that Samantha really resolved to do was to make sure that we didn't have others on camera guessing at what Britney was thinking.

VFD: Yeah,

Mary Robertson: They might tell you what they saw. And they might tell you what numbers she hit on the Billboard charts. But they're not going to tell you: …and then Britney felt happy! Or: And then Britney felt sad! Because only Britney knows, right? We were very deliberate.

And again, Samantha really took the lead and was very deliberate in making sure that we weren't rendering her feelings from a distance. Distance creates inaccuracy in some ways.

And then, of course, we tried. We tried to get close to her. We put in many requests to speak with her. And you see the card at the end of the film that shows that.

VFD: There were a few people that weren't very interested in it, right? Have you had anyone reach out since it came out in March… or February?

Mary Robertson: February.

VFD: So it's been a while, right?

Mary Robertson: Yeah. And, yes, there have been a lot of new sources who have engaged with us and we’re very grateful for the way in which they're helping us get closer to the truth.

VFD: Does that mean there's another film to come out?

Mary Robertson: I would say, Brad, that it could happen…

VFD: OK, OK… we can read between the lines there…

So what was it like between February, when it came out, and now, where the depth of your storytelling is increasing without you actually telling more story?

Mary Robertson: It has been a singular and wild ride for all of us who worked on the film. The responses are not like anything that we've anticipated or ever experienced before, and probably will again.

But Liz and Samantha and Joe Coscarelli have continued to report on this and they did publish this great print piece the day before Britney’s public testimony. And then they've continued to publish a few items in the days and weeks since. So we haven't put out another film, but we are very much still on the story and are hoping to really advance the public's understanding – and our own understanding – of what the truth is here.

VFD: And how did you approach the Free Britney movement? I think of it as someone who has a background in working in journalism and in media and I'm just like: that is dangerous. Well, not dangerous – but something that can be tough to navigate I imagine: Fandom. Particularly when it's fandom that is accusatory, regardless of what you believe. What was the approach there?

Mary Robertson: Y’know, you can't tell the story of Britney and you can't tell the story of her and the conservatorship without chronicling the Free Britney movement. They have had real impact, certainly. So it was never a question of whether we would include them.

But I think your question gets to the heart of how we render some of the claims – and we just made sure that we fact checked every claim that was made on camera. And Liz Day and her colleagues – she had a small team – they were responsible for fact checking every claim. So that means that if there's a clip from TMZ in our film we've fact checked TMZ’s claims before we put them in our film. We don't want to be responsible for, or propagating something, which isn't true or accurate. So that holds for the fans and their claims as well.

VFD: Yeah, OK. Well, I wanted to ask you – I feel like we've we've gone down the Britney rabbit hole – but I had a curiosity about the other part of your life. It’s a bit of a turn. But seriously: what is the process of the Emmys? Because, like, you don't get the opportunity to talk to people, or people who have won them, about it that much. And I have literally no idea how it goes. Do you get a black envelope with a gold stamp on it or something? Like, what is the process?

Mary Robertson: Haha, well, there are many talented professionals whose job it is to navigate these missions and campaigns. Really talented individuals who work hard at it. I am not one of them.

But there's all types of Emmys: there's daytime Emmys, and creative arts Emmys, and primetime Emmys, and music and documentary Emmys. I mean, one thing that awards professionals and their colleagues often work to determine is where it makes the most sense to submit. And I've worked on frontlines that were nominated for Emmys, news and documentary Emmys, and it does always feel good to receive a degree of recognition. “The Weekly” – I was part of the team that produced that and received nine nominations and four wins.

VFD: Oh yeah, just a handful. It’s like: whatever.

Mary Robertson: Y’know, there's a joke within the documentary community about the news and documentary Emmys, I think, which is that we sometimes call it the nerd prom. There’s lot of wonky types getting dressed up.

The year that “The Weekly” won was, of course, in the midst of the pandemic. So there was no nerd prom. We were on our couches. And we're so grateful for that recognition. I think that was a fledgling enterprise and our ambitions were high. It was really hard work. And receiving that accolade at the end of that run meant so much to me and the whole team, and it really just helped us see that some of what we have been trying to do, arguably, we'd accomplished. It was great.

Film and television is made by an army. I think a lot of print journalism is, too, and there's editors and there's copy editors involved and there's graphics and there's photo work. But my colleagues in print who have been working alongside me in film and television are perpetually astonished at how many people it takes to make television. And it really, really takes so, so, so many people. And often it's so many people who are working at the same time at a similar objective. There's challenges around communication.

In any case, the point I'm getting at is that it's hard work. It's a slog for many. It's often very rewarding. But these little bits of public recognition – it’s wonderful when they're distributed broadly and across the full team, and it helps put a little gas in our tanks.

I think impact is the ultimate fuel. But sometimes one feeds the other. If you received some public recognition in the form of awards, then suddenly more people are going to find your film and go watch it and engage with the subject matter. And the potential for impact increases.

VFD: Yeah, it works out well. It's not a bad thing – we could say that pretty definitively.

Well, I'm looking at the time and I don't want to keep you much longer.

Mary Robertson: Yeah, you need to get some shut-eye.

VFD: Well, I don't know if you know, but we're in lockdown in Sydney, in Australia. Which is gonna sound bizarre to you in the US, because we have around 200 cases. But here that's a big deal.

So like: yes, I’m up late. But also, I'm at work already! Things are fine.

Mary Robertson: How is the vaccine distribution in Australia?

VFD: Oh, oh, it's terrible. Actually terrible. And if we had a different mediascape that was structured differently – it's pretty much that 70% of it is one company down here. And that is Murdoch. So our conservative-leaning government doesn't get a lot of negative press, or front page negative press, and I think if the shoe was on the other foot and we had a more Liberal government stuffing up the vaccination rollout, well…

It is pretty unreal. We've got 25 million people. It’s not huge. But it is what it is. I'm not eligible yet. I'm just hanging out waiting. Have you had the vaccine?

Mary Robertson: I’m waiting for my children to get vaccinated because they're going to return to school in the fall and I’ll feel a lot better if they are.

VFD: This is the world we live in now.

Mary Robertson: I had colleagues who relocated to Australia at the beginning of the pandemic, and I would look at their Instagram and it was so idyllic.

VFD: Well, yeah, that's true, comparatively. Especially if you're in New York City. I remember there were snowstorms in New York City right at the beginning of it, and people were just locked inside. I’m not jealous of that.

But yeah, thank you so much for this. I really appreciate it. I know I've said that a few times. But I really do.

Mary Robertson: I think the Emmy nominations will be announced on Monday.

VFD: Yeah, I know. And a little bird told me there's a pretty good chance that maybe, “Framing Britney Spears”….

Mary Robertson: Yeah, you never know. You never know.

VFD: Yeah, well, good luck with that. And I'll think of you when it happens.